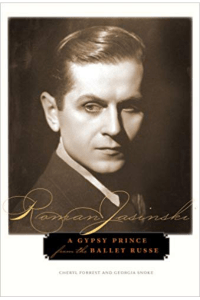

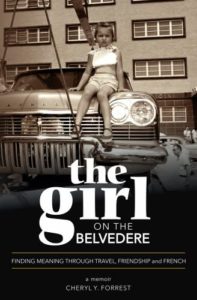

My fellow ballet historian Georgia and I were taking the first of our many trips to research the life of Roman Jasinski, star of the Ballet Russe, when that company was a world-wide phenomenon. We were writing the story of his life, and this trip would take us deep into the libraries of Monte Carlo and Paris.

The airline lost my luggage, so I slept in my clothes that first night in Monte Carlo, having been assured that my luggage would be delivered the next day by helicopter. Of course, by helicopter, how else, in this glamorous town? It took me no time to dress the next morning, which is one advantage of lost luggage.

After breakfast, Georgia and I made our way toward the famous Monte Carlo Casino which held the theatre and dance archives. Along the way, we passed a beautiful woman standing in front of the celebrated Café de Paris wearing a long red gown, her flowing blonde hair held back by a matching headband. A crowd had gathered to gape at her, and Georgia and I exchanged looks, silently surmising that she must be a famous young starlet.

I reflected on what life had been like at this café in more glamorous days, before the advent of tourists with their T-shirts, shorts, flip-flops, and ballcaps. It had been frequented by artists of all types, by the rich and famous, by the likes of the current-day glamorous blonde woman and other locals who took pride in their looks. Good grooming was still a matter of politeness toward others here in Monte Carlo. As we passed the Café,I realized that my rather austere business pantsuit was no stylistic match for those fortunate enough to live and work on the Côte d’Azur.

We had an appointment in the archives of the casino, as Roman Jasinski had danced in its theatre many times in the 1920s and 30s. We entered the Casino and gaped at the walls adorned in marble and gilt, and asked a security guard where to find les archives. He pointed to a massive marble staircase. Up we went to the darkened door at the top. It was the marketing office, and it was empty. We descended and asked the guard again where the archives might be located. Again, he pointed to the staircase. We marched up and examined the same dark office. Coming down once again, a female voice startled us by saying, “Mesdames, Mesdames!” We whipped around and found that a young woman had appeared out of nowhere on the staircase behind us. After we introduced ourselves to this young historian, she turned and opened a hidden door in an alcove.

The passageway behind the door was dark, barely lit, like the backstage of a theatre. There was a huge oval cast iron staircase, with large C-clamps at some of the turns, perhaps holding it together, perhaps lending it strength. The inset wooden treads were worn down and sagging in the middle. This building was built in the 1860s, and the staircase appeared to be original. I was immediately at ease. The dimly lit area was just like every backstage in every old theatre in which I had ever danced. We ascended several floors with the historian, and entered her office, blindingly bright with sunshine streaming in against white Formica surfaces. What a contrast to the darkened interior! The archival office was modern and austere.

Madame brought us a treasure trove of programs and photos that pertained to Roman Jasinski, many of which we had never seen. We spent some time examining photos and requesting reprints of old French journal articles and reviews. We chose one photo of the 1932 ballet La Concurrence, with Roman Jasinski wearing a straw hat, a suit with a contrasting lapel and a large floppy black bow tie. He was carrying a cane while partnering a beautiful young dancer who was bent backward over his extended arm. Jasinski was so young, so handsome, and reportedly the most sought-after man in the company. There he was, 25 years old, the lined face and cares of the man I knew years later magically erased.

Growing up in the ballet studio of Roman Jasinski, we had always been surrounded by posters and photographs of the Ballet Russe, but the artifacts on the table before us were mostly unfamiliar. These were from the early days of the company, before he was a star, when he had only one suitcase to his name. “It was only half full,” he had told me. “I had some books and just a few clothes. One suit was on me and a black suit for church was in the suitcase along with one pair of shoes and a few shirts. That’s all.” He had been chosen for La Concurrence by George Balanchine himself, the future founder and visionary artistic director of the New York City Ballet. Heady days indeed.

We observed, we exclaimed, and we imagined the life Jasinski had led. The evidence was spread out on the table before us; it was a glimpse into a now-extinct world. Madame appeared and announced that it was time for lunch and that the archives were closing. This seldom-seen archive was suddenly and irrevocably lost to us. Georgia and I gathered our materials, thanked Madame profusely, and descended, not knowing which door led back to the marble staircase. We picked one, and found that we had materialized in the heart of the casino behind two burly armed guards with earpieces. They whirled around, hands on weapons, and were startled to find two laughing women of a certain age. They gave us hard stares, but let us pass.

This was a famous room, a James Bond room, with cherubs, gilt, and marble. It was still early in the day—only 1 p.m.—and the room looked a little garish in the harsh daytime light. One-arm bandits, standing shoulder to shoulder against the wall, obscured the beautiful tall windows with views of the Mediterranean. There was no black-tie finery; the tourists were casually dressed, which was allowed before the casino opened for gambling later in the day. We looked around this beautiful room, taking it all in, and finally departed, our long-anticipated day in the Monte Carlo Casino behind us. It was my first visit to Monte Carlo, and my one-and-only visit behind the scenes.

I would love to read your comments! Please feel free to leave a short note.