I was with my friend Amber in Paris one afternoon several years ago. We were there with our Tulsa Community College French class, and had been given some free time. Amber is an artist, and there was one thing and one thing only she wanted to see in the Louvre—Winged Victory. We found it, and sat on one side, studying it, while the other tourists milled around us, chatting and taking photos.

We stood, went down several wide steps in front of Winged Victory, and up another set of steps to the other side of the sculpture for a different view. As we turned to leave, I happened to see an older man with grey hair and glasses slip on the marble stairs. He went down hard, and cried out in pain. I approached him and offered help. He responded with a monologue:

“Call an ambulance! I need a wheelchair! I need a stretcher! It hurts. I broke my arm. Can you take a picture of this? What’s your name? Call them again! It always takes three times to get through. I need a stretcher! Tell them to call an ambulance. I need a wheelchair, can you get one? Can you call? Where are they? They need to call right now. It hurts! Thanks so much. Where are you from?”

During this outburst, I had yelled “Monsieur!” across Winged Victory’s viewing area and gotten the attention of a museum guard. I explained to him in French that the gentleman needed help. Another guard arrived and asked what had happened. I explained to the second guard what I had observed, and he asked me to stay until the official interpreter arrived.

The monologue of the injured man continued unabated. Amber and I left when the interpreter arrived with reinforcements. Months later, Amber received a thank-you note from one of the injured man’s traveling companions. His treatment in a Paris hospital had been courteous and complete.

Amber and I decided that day that we had had enough excitement in the Louvre, and left the museum to sit near a fountain in the Tuileries Garden. We propped up our feet on empty chairs and took a short nap.

Afterward, as we were walking along the river, I heard screaming and honking. I looked at the busy intersection near the Place du Châtelet just in time to see a motorcycle speeding along next to a city bus. The bus was inching ever closer to the lone rider, who continued to scream and honk. I watched in fascinated horror as the bus sideswiped the motorcycle. In what seemed like slow motion, the cycle went under the bus while the rider rolled away in the opposite direction. He came to a halt perhaps ten feet away from the bus, tucked into a ball, resting on his ankles and knees, his hands over his head.

The bus stopped, the driver descended, stared uncomprehendingly at the victim, then at the motorcycle trapped beneath his bus. People nearest the victim ran to the motorcyclist’s aid and alerted traffic to go around. Several witnesses pulled out their cell phones and called for help.

Amber and I walked on, certain that the cyclist was in good hands. We looked at each other in disbelief. What a day in Paris.

One Saturday a year later, my husband John and I drove to a ranch several hours away to visit our son Bennett and our grandson. I took special care that morning, having had hand surgery the day before. My left hand was well-wrapped in surgical dressings and I had strict instructions not to use it. What harm can there be, I thought. I’m just going to sit, visit with Bennett, and play with my grandson.

It was pouring that day, so we mostly sat inside. I rested on the sofa and talked with my five-year-old grandson about what was going on in his life. The men—John, Bennett, brother-in-law David, and his friend stood in the kitchen and spoke of manly things. John and I eventually said goodbye and drove back to Tulsa as the afternoon began its descent into evening.

We were watching Netflix when I decided I needed a heating pad for my always-aching lower back, a gift from ballet training. I walked with assurance into our darkened bedroom. I have always been confident in my foot placement, having fallen only once since childhood. That occurred on stage during the premiere of Tulsa’s first Nutcracker when my foot became entangled in my Arabian costume.

Suddenly I was falling again. Too late, I remembered that I had pulled out a box from under the bed that contained my seldom-used sports shoes. For this rainy day I had selected what we call “duck shoes” from our days in Virginia. I had forgotten to shove the box back under the bed. I went down hard, hitting my head on the nightstand as my right unbandaged hand flew out to break my fall.

Stunned, I lay there for a few seconds then realized I could not get up without help. My head hurt and I had only one unbandaged hand available, and that one was now injured. I called for John.

Only Nutmeg the dog responded. She came in and looked at me, then left. I called again. John came in, looked at me, and also left.

I called again, thinking that even though I thought of myself as young, maybe I needed one of those emergency necklaces because I wasn’t going to get any help from my dog or from my husband.

John did return a few seconds later, flipped on a light, and asked what had happened and if I was injured.

“Why did you leave me?” I whined. “I’m hurt.”

“I was eating that leftover chicken,” John said, “and I was afraid that Nutmeg was going to eat the bones.”

“Okay. But I’ve hurt my good hand,” I said. “I can’t get up.” He helped me sit on the bed, examined my hand and wrist, and asked, “Do you need to go to the hospital?”

It hurts, I thought. It hurts. I need a doctor. “I think I need to have it looked at,” I said. “Hopefully it’s just a sprain.” It really hurts, I thought.

My husband, who is the Chief Medical Officer of our hospital system, called ahead to alert the Emergency Room that we were coming.

After I was shown into a room, a nurse came in. “You think you’ve broken your wrist?” she asked, looking at my bandaged hand.

“No, not that one,” I said. “This one,” I said as I held up the other hand.

“Oh dear,” she said. “I’ll let the doctor know.”

They took me to X-ray, and afterward informed me that my wrist was broken in three places. My arm was set in a soft cast, and set in a plaster cast several days later by an orthopedic surgeon—the same surgeon who had operated on the other hand a few days before. He just looked at me and shook his head.

Several difficult weeks ensued. I needed help dressing, cutting my food, and getting situated each day for my one-fingered online life. During those inactive weeks my mind returned again and again to the man in the Louvre holding his broken arm, and to the man on the motorcycle rolling away and covering his head after the bus hit him.

I couldn’t hear what the man on the motorcycle had said, but I imagine it was something like, “It hurts. Call an ambulance. Where is the doctor? I need a stretcher. I need to go to the hospital. Where is the ambulance? It hurts. I need a doctor.”

Three accidents, three injured, with at least two of us fully recovered. I think of those two injured men in Paris, and mentally wish them well. I hope that the three of us have learned to beware of large sculptures, moving buses, and plastic boxes carelessly left lying about.

Nicole Morgan

Great article!

Lynne

I’m so sorry about your wrists and hope they are all better now. How creative to take three sad situations and put them together for a short story of empathy and perspective.

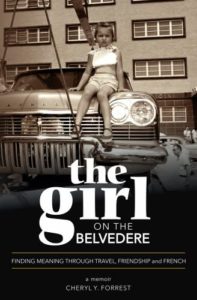

Cheryl Y. Forrest

My wrists and hands are fully healed – all is well! Of all the days I’ve spent in Paris, that one certainly stands out. Thanks for reading!